The tides of strength beyond the shoreline, Stories from Unguja and Pemba

By Neema Said

The night before my flight felt endless, a mix of nerves and excitement tossing through my body like waves in a restless sea. When the alarm finally screamed to life, I was already halfway out of bed, had prepared myself, and headed to the airport. The plane was tiny, the kind that makes you second-guess your life choices mid-air, but adventure waited ahead. Minutes later, I touched down in Pemba, the island of cloves, its sweet scent wrapping around me like a warm welcome.

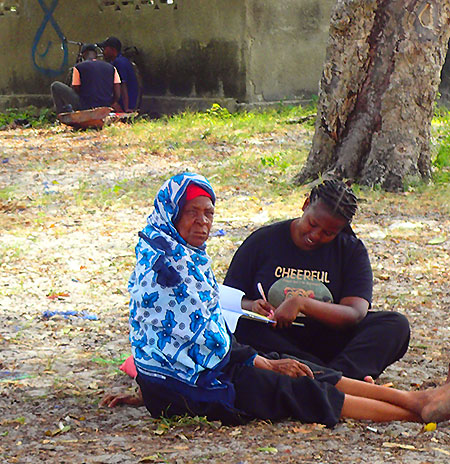

I had never been to Pemba before, so being part of this collaborative project between the Royal Agricultural University and the University of Dar es Salaam felt surreal. I wasn’t just traveling; I was stepping into stories, lives, new experiences, learning, and landscapes that had long existed. I was part of a group and a project that aimed to understand how artisanal fishers in Pemba, Unguja, and Mafia are navigating the harsh realities of climate change. Their ways of life being under threat from the mounting pressures of coral bleaching, warming seas, and unpredictable winds. I was excited to join the team led by Prof. Mark Horton, Dr. Annalisa Christie and Prof Elgidius Ichumbaki, as a research assistant, taking project photos, helping facilitate the creative workshops with women, and writing the script that is an output of the project. All I can say is we aimed to genuinely listen to the voices of coastal communities as they spoke about the sea, their work, and the silent changes creeping into their daily rhythms.

I also participated in conducting interviews and simply sitting with people as they unfolded their lives with me. A conversation that stuck with me was of a man who said, "Bahari haimtupi mtu" meaning the sea never abandons anyone. His words carried weight. For these communities, the sea isn’t just water; it’s heritage, livelihood, and identity, and their means of survival.

I’ve always seen the sea as my free therapy session, a place where I could sit, listen to the waves, and feel my soul soften. I knew people fished, of course, I eat fish in town. But this journey revealed something deeper: the sea is not just a backdrop or a food source. It is life itself for many.

I was struck by the women, strong and determined, collecting oysters, trochus shells, sea cucumbers, along with other marine resources and farmed seaweed, to feed their families and earn income. Some are doing this after their husbands left for what's known as “Dago” temporary fishing camps, where men live for weeks, sometimes never returning. One young woman started seaweed farming at 15 to raise her siblings, and she pleaded that “Itunze sana bahari ili na wewe ikutunze” meaning take care of the sea so it can take care of you. These words were not metaphors but truths about survival. Others now want to fish like men, heading into deep waters and breaking traditions out of necessity.

Yet their work remains underrepresented. Museums and official records rarely acknowledge their roles. Some women feel men are encroaching on their space, and others are happy with it. I also loved the rhythm of their local speech and how they speak; they mark calendars with names like Mfungo Tatu and Mwezi Tisa. In Chwaka, I learned about the annual dua ya jiji, a village cleansing ritual.

This experience did more than take me to new places; it opened my eyes, widened my heart, and gave my curiosity a new direction. I didn’t just listen to women’s stories. I got the chance to join them. I went out and took part in their activities: walking the muddy shores to harvest seaweed (on low tides or “maji yakitoka” as they termed it), learning how they collect oysters, and feeling the weight of that work in my own hands. It was humbling. These women carry so much for their families, their communities, and the sea itself. It also lit a spark in me. I'm now writing an article titled “Women in the Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean Islands in Tanzania: A Marine Cultural Heritage Perspective”. Some women hope their children won’t have to do the same work unless they have no other option, because they know how difficult and unstable it can be.

This journey changed how I see the ocean. It’s not just something to admire; it’s something to protect. We owe it to those who live by it to act: to restore mangroves, keep plastics out of the water, and fight illegal fishing. The sea is more than water. It is memory. It is survival. It is home.